LCARS and the AI Control Revolution: Why Your SaaS Needs More Than a Chatbot

Legacy SaaS platforms are slapping chatbots on interfaces and calling it AI. What users actually want is Star Trek's LCARS—conversational control of complex systems.

The Enterprise Bridge Isn't Just Pretty Panels

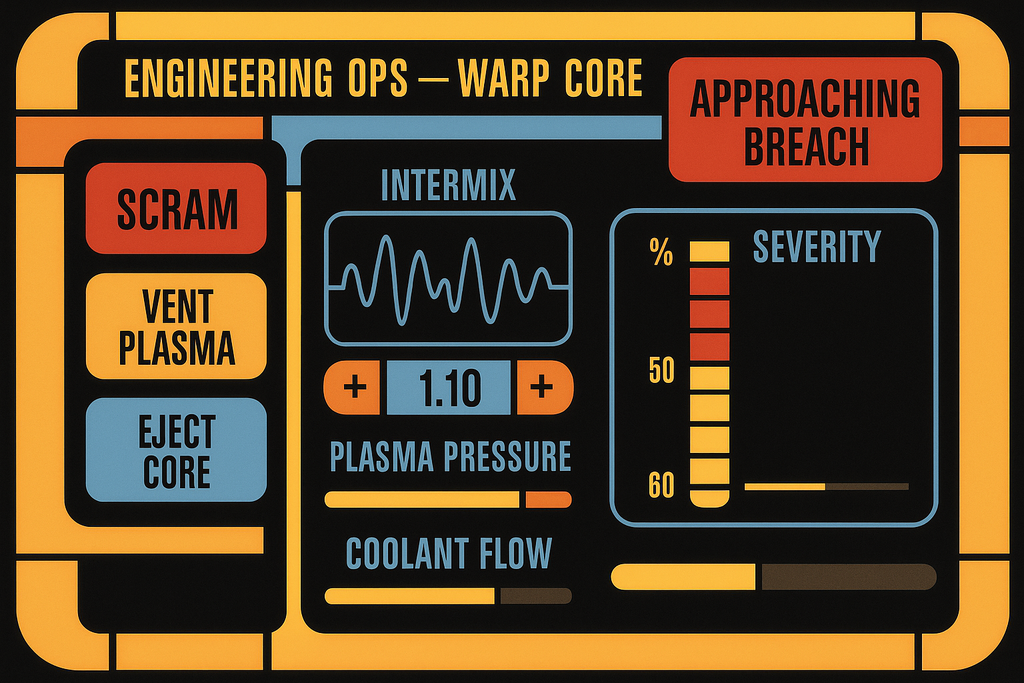

Picture the bridge of the USS Enterprise. Geordi LaForge approaches a console, speaks a command, and the ship's warp core adjusts its matter-antimatter reaction ratios. He doesn't navigate through nested menus or drag sliders around. He doesn't fill out forms requesting permission to modify dilithium chamber parameters. He tells the computer what he needs, and it happens.

That's LCARS—the Library Computer Access and Retrieval System. Part of Star Trek: The Next Generation's aesthetic package alongside mauve chairs and Counselor Troi's wardrobe choices, LCARS represented something profound that we're only now beginning to understand. It wasn't just an interface. It was conversational control over irreducibly complex operations.

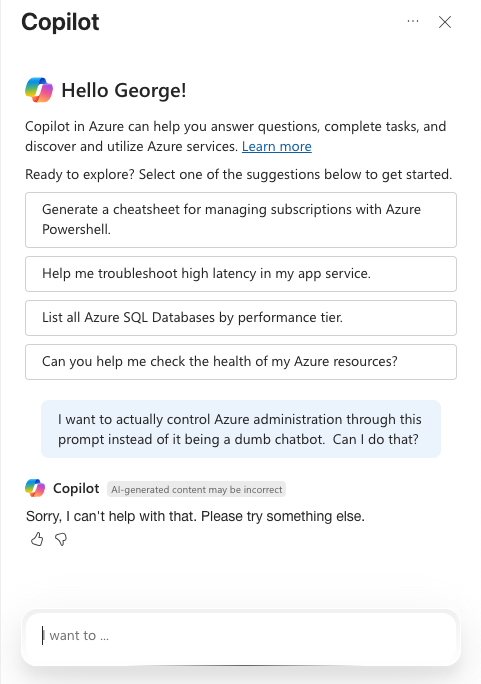

Today's enterprise software vendors have discovered AI, sort of. They've bolted chatbots onto their existing interfaces and declared victory. These "copilots" can explain features, suggest next steps, maybe generate some reports. What they can't do is actually operate the software. They're tour guides in a factory they're not allowed to touch.

The Embedded Versus Controlled Distinction

Here's the thing most SaaS companies haven't grasped: there's a canyon between AI-embedded and AI-controlled systems.

AI-embedded means you've added some intelligence to your existing paradigm. Your forms might auto-complete better. Your search might understand synonyms. Your chatbot might explain why you're getting an error message. But you're still clicking, dragging, typing into fields. The AI is a passenger in your manual process.

AI-controlled flips the relationship. You express intent, and the system executes. Not through pre-programmed macros or rigid command syntax, but through genuine understanding of your goals and the ability to orchestrate complex operations to achieve them. The AI becomes the pilot while you become the mission commander.

Consider the absurdity of current "AI-powered" interfaces. You ask the copilot to update customer records, and it responds with step-by-step instructions for navigating to the customer module, clicking edit, modifying fields, and saving changes. It knows exactly what needs to happen. It can see all the controls. It just can't touch them.

It's like having a expert chef who can only point at ingredients while you fumble with the knife.

Why LCARS Got It Right

The genius of LCARS wasn't the colorful panels or the satisfying beeps. Those were just the aesthetic wrapper around a deeper insight: when controlling complex systems, the interface should convey status and accept intent, not micromanage actions.

Watch any Next Generation episode where they're managing a crisis. Data doesn't manually adjust hundreds of parameters to stabilize a warp core breach. He tells the computer what outcome he needs, and the system handles the implementation details. The interface shows him what's happening—plasma temperatures, containment field strength, antimatter flow rates—but he's not individually tweaking each variable.

Modern enterprise software does the opposite. It makes you the implementation layer. You become the mechanism that translates business intent into a thousand individual clicks and keystrokes. The software might be powerful, but you're operating it like a telegraph operator tapping out Morse code.

The chatbot sitting in the corner, offering helpful suggestions while you perform this manual labor, only emphasizes the absurdity.

The Irreducible Complexity Problem

Stephen Wolfram has this concept about computational irreducibility that explains why enterprise software feels like operating a steam engine. Some systems, he argues, can't be simplified beyond their basic rules. You can know the starting conditions perfectly, understand the laws governing the system completely, and still have no shortcut to predict the outcome. You have to actually run the computation to see what happens.

The three-body problem is the classic example. Three celestial objects, gravitational forces between them, initial positions and velocities all known. Simple Newtonian physics. But if you want to know where they'll be at time T=100? There's no formula that gets you there. You have to simulate each moment, step by step, watching the chaos emerge from deterministic rules.

This gets dangerously close to simulation hypothesis territory—the domain of well-meaning cranks and philosophy majors who've read too much Philip K. Dick. But Wolfram knows his mathematics better than I do, which is a low bar, and likely better than any language model, which might or might not be a higher one. His point stands: some processes resist reduction.

Managing enterprise (or Enterpise D) operations hits this same wall. Running a global supply chain, managing regulatory compliance across jurisdictions, orchestrating financial operations—these aren't tasks you can reduce to simple formulas. Each decision influences every other decision in ways that only become clear through execution.

Traditional interfaces handle this complexity by exposing every lever and dial to the user. You get massive configuration screens, endless form fields, nested menus that would make Inception jealous. The complexity doesn't disappear; it just gets pushed onto the human operator.

LCARS suggested a different approach: acknowledge the complexity but abstract the interaction. The Enterprise's computer wasn't simple—it managed everything from life support to weapon systems to holodeck safety protocols. But crew members didn't need to understand the implementation details of transporter pattern buffers to beam down to a planet.

They expressed intent: "Transport the away team to these coordinates."

The computer handled the rest: pattern analysis, Heisenberg compensators, matter stream targeting, molecular reconstruction.

That's what AI-controlled systems should do. Not hide complexity, but handle it.

The Coming Interface Rebellion

Users are getting tired of being the integration layer between their intent and their software's capabilities. They've experienced conversational AI that understands nuanced requests. They've seen demonstrations of agents that can book flights, write code, and analyze documents. They're starting to wonder why their enterprise software—which costs orders of magnitude more—feels like operating a steam engine.

The rebellion won't be sudden. It'll start with users finding workarounds. They'll use unauthorized AI tools to generate the data they need, then manually enter it into the official system. They'll build shadow IT solutions that actually respond to voice commands. They'll share spreadsheets that work better than million-dollar platforms.

Eventually, some vendor will realize what users actually want isn't another embedded assistant but genuine AI control. They'll build systems where you can say "reallocate Q3 budget to account for the supply chain delays" and have it actually happen—with all the complexity of permissions, approvals, and audit trails handled invisibly but correctly.

The Industry's Awkward Adolescence

Let's be fair to the SaaS companies desperately gluing chatbots onto their interfaces. The industry is barely out of diapers when it comes to AI integration. The paradigm shift is happening so fast that sticking to your knitting while the world reshapes itself is almost understandable.

Consider the velocity of change. A year ago, GitHub Copilot was essentially autocomplete on steroids—impressive if you'd never seen it before, quaint by today's standards. Now, a single prompt can generate a complete replica of the 1985 Amiga BOING demo, complete with checkered ball physics and that distinctive metallic sound. That's not evolution; that's punctuated equilibrium with a rocket strapped to it.

The entire industry is caught in a bizarre moment. Companies fixate on model benchmarks like medieval scholars debating angels on pinheads. Product managers desperately try to fold "AI" into existing applications like trying to retrofit a jet engine onto a horse carriage. Meanwhile, mid-career software engineers are experiencing existential dread as they watch the tedious parts of their jobs evaporate.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: developers who aren't adapting to AI-assisted development are becoming as relevant as buggy whip manufacturers in 1925. They're perfecting their craft just as the world stops needing it. The ones who survive won't be the ones who write the cleanest code, but the ones who learn to orchestrate AI systems to write clean code at superhuman speed.

The Electric Car Problem

We're living through a classic case of the electric car problem. The technology for AI-controlled systems exists today, just like battery-electric vehicles were perfectly feasible in 1900. What's missing isn't the fundamental capability but the infrastructure and economic will to implement it at scale.

Consider Data from The Next Generation. In 1985, the computational theory for building an android was essentially extrapolatable from existing principles. Neural networks, decision trees, pattern recognition—all understood, just not implementable with 1985 hardware. Today we have the hardware. We have models that can reason, plan, and execute complex tasks. What we don't have are software architectures designed to let them actually control things.

Current SaaS platforms are like those early electric cars that lost to gasoline not because electricity was inferior, but because the entire infrastructure was built around internal combustion. Gas stations everywhere, mechanics who understood carburetors, supply chains for petroleum products. The electric car was better in many ways—simpler, cleaner, fewer moving parts—but it couldn't overcome the installed base.

Similarly, our enterprise software infrastructure assumes human operators. Permission models, audit trails, UI frameworks, API designs—everything presupposes a person clicking buttons. The chatbot sitting alongside this infrastructure, helpfully explaining what each button does while you click it, is like mounting an electric motor next to a gasoline engine and calling it hybrid technology.

What we need isn't new science. We need the architectural courage to build systems that assume AI control from the ground up, not as an afterthought but as the primary interface. The technology exists. The will, apparently, does not.

The Path Forward

The transition from AI-embedded to AI-controlled won't happen overnight, but it'll happen faster than most organizations expect. It requires fundamental architectural changes, not just API connections to language models. Systems need to be built with programmatic control as a first principle, not a bolted-on afterthought.

The vendors who figure this out first will have an insurmountable advantage. While their competitors are still benchmarking models and adding chatbot widgets, they'll be shipping systems that actually respond to intent. While others are training users on workflows, they'll be adapting to how users actually think.

The future of enterprise software isn't better forms or smarter tooltips. It's systems that understand intent and possess the agency to act on it. It's LCARS, minus the mauve chairs.

Your next SaaS platform shouldn't just have AI. It should be AI-controlled. Anything less is just a chatbot watching you work—a very expensive backseat driver who knows the way but can't touch the wheel.

Geordie

Known simply as Geordie (or George, depending on when your paths crossed)—a mononym meaning "man of the earth"—he brings three decades of experience implementing enterprise knowledge systems for organizations from Coca-Cola to the United Nations. His expertise in semantic search and machine learning has evolved alongside computing itself, from command-line interfaces to conversational AI. As founder of Applied Relevance, he helps organizations navigate the increasingly blurred boundary between human and machine cognition, writing to clarify his own thinking and, perhaps, yours as well.

I couldn't wait for the 24th century, so I adapted a TNG combadge into the interface of my dreams. Unfortunately, this website does not permit linking to youtube in comments, or I'd show you. I'm not a youtuber so I'm not farming likes, but I do have a video up demonstrating what I built. Google "GummiBot9000 a smol demonstration" if you wanna see it. At the moment, I'm pretty sure I have the most functional TNG combadge on the planet.